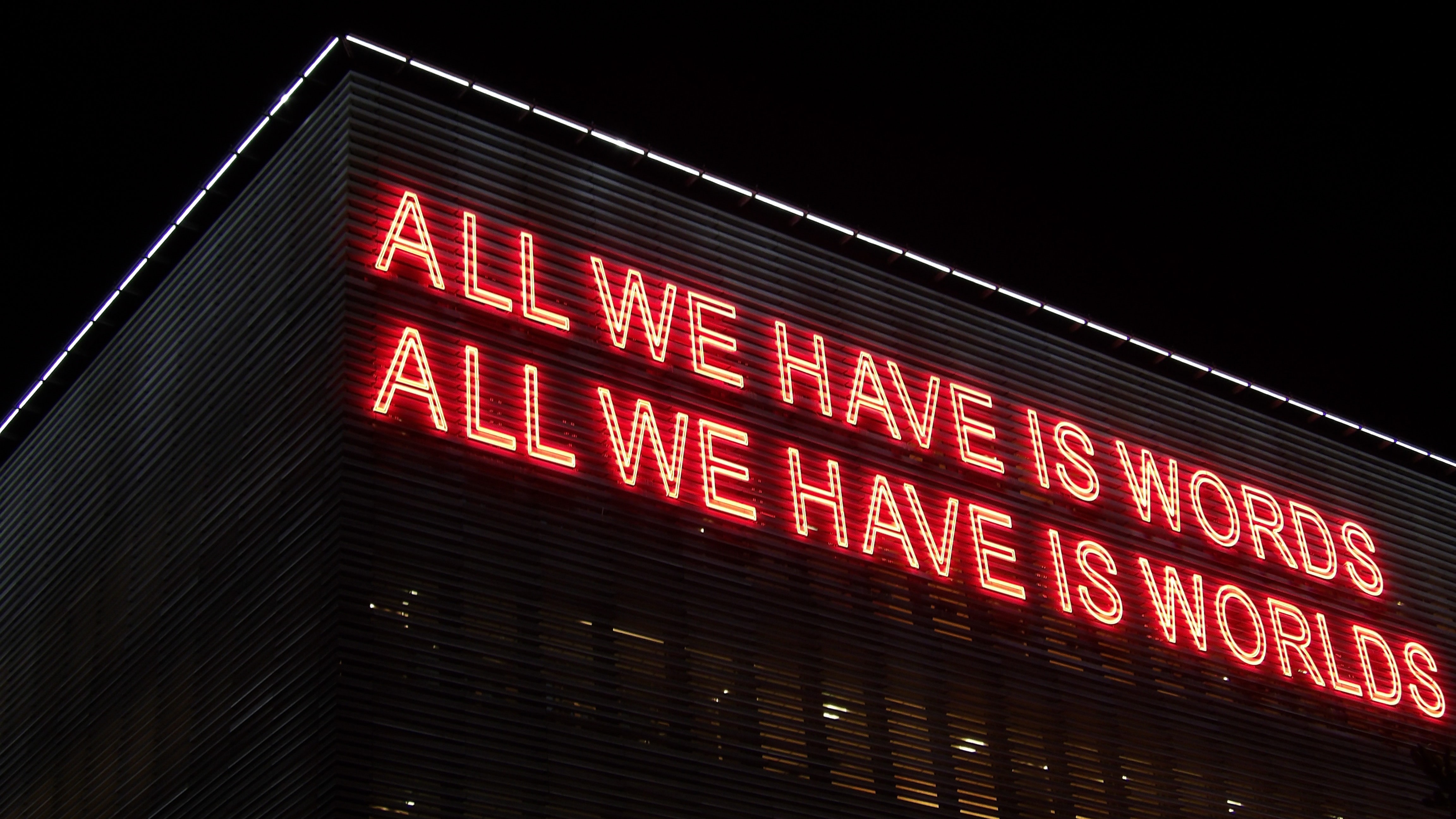

Reflections on ESOMAR 2022: Brave New Words

By Lucas Cunha

Almost a hundred years ago, the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote in his seminal Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus that, "The limits of my language mean the limits of my world." Wittgenstein was referring to the relationship between language, philosophy and science, but this is an idea that seems to have spread its influence to different parts of our society.

Take, for example, marketing. It can be defined as the way brands and companies push their products or services to their target audiences. In essence, it's how they communicate with us. So, in a world that has seen such drastic changes in such a short span of time (think of how COVID seems somehow both yesterday's news and an ever-present threat) should the language that these same brands and companies use to reach their audiences also change? And, if so, what does this new language look like?

This was the question Cato Hunt, Fiona McNae, Julius Colwyn, Anouk Bergner and Sui Lai Kang (who all work at Space Doctors, a British consulting firm part of InSites Consulting) decided to tackle in the paper they presented at the latest ESOMAR conference, in September of this year. Entitled New Worlds Need New Words — Why we must change the language of marketing, the paper (which also mentions the famous Wittgenstein quote) argues that, for instance, “sustainability”, long a go-to word for brands and companies that suddenly noticed the need to talk about issues like climate change, is out. “Regeneration” is in. As they point out, “We need to create a world that restores the natural systems we rely upon for survival.”

They explain how several marketing expressions might hide outdated concepts and ideas that should be dismissed if the brand wishes to keep up with the times. For example, “positioning territory” could be interpreted as “a concept of domination and rule, bringing with it assumptions of conflict and invasion. It is the aggressive language of the colonial ruler; entering a territory to own it, claim it and prevent all others from existing within it.”

In their vision, this change of tone will be accelerated by three sectors of society. Number one is the public — the paper notes how “young people worldwide view the planet’s wellbeing as of greater importance than economic opportunities.” Second comes our debilitated supply chains, ravaged by both war and pandemic. In third place, we have governmental and regulatory bodies, which “are becoming more active in guiding business towards regenerative practices by legislating around impact, investment and integrity.”

Interestingly, the authors also offer a roadmap of how to discard old market-speak and transition into new ways of thinking (and talking) about marketing: instead of “linear mechanisms”, which reeks of the industrial revolution, why not try “holistic process”? Instead of “novel disruption” go for “resilient adaptation.”

In the end, the authors seem to reach a conclusion that barely leaves room for doubts. They believe the need for change is real, urgent and not merely superficial. “Every organization will need to find a vocabulary which resonates for them, and which inspires others to use it. If we just move words around at the surface, then we simply greenwash, perpetuating ideas that represent our current failing system.”

They go on to say that, “Instead, we need to change the metaphors and meanings we use, cocreating a different language which helps us embody new assumptions and create new possibility together.”